A Doctrinal Evaluation of the Anti-Lordship Salvation Movement: Part 1

Introduction and Historical Background Leading up to the Anti-Lordship Salvation Movement

Not long after I became a Christian in 1983, the Lordship Salvation (hereafter LS) controversy arose. This was a movement against “easy believism” (hereafter EB). The climate was ripe for the controversy because churches were full of professing Christians who demonstrated little if any life change. Members in good standing could be living together out of wedlock, wife abusing drunks, and shysters to name a few categories among many. Sin was not confronted in the church.

Of course, no cycle of Protestant civil war is complete without dueling book publications. Without naming all of them, the major theme was that of faith and works. John MacArthur Jr. threw gasoline on the fire with The Gospel According to Jesus published in 1988. This resulted in MacArthur being the primary target among the so-called EB crowd.

During that time as a new believer, I was heavily focused on the issue, but was like many others: I rejected outright sinful lifestyles among professing Christians while living a life of biblical generalities. In other words, like most, I was ignorant in regard to the finer points of Christian living. I resisted blatant sin, and in fact was freed from some serious temptations of the prior life, but had little wisdom in regard to successful application.

We must now pause to consider what was going in the 80’s. Christianity was characterized by two groups: the grace crowd that contended against any assessment of one’s standing with God based on behavior (EB), and the LS crowd. But, the LS group lived by biblical generalities. Hence, in general, both groups farmed out serious life problems to the secular experts. This also led to Christian Psychologist careerism.

This led to yet another controversy among American Christians during the same time period, the sufficiency of Scripture debate. Is the Bible sufficient for life’s deepest problems? Again, MacArthur was at the forefront of the controversy with his publication of Our Sufficiency in Christ published in 1991. Between 1990-1995, the anti-Christian Psychology movement raged (ACS). The primary lightening rod during that time was a book published by Dave Hunt: The Seduction of Christianity (1985).

In circa 1965, a young Presbyterian minister named Jay E. Adams was moved by the reality of a church living by biblical generalities. The idea that the church could not help people with serious problems like schizophrenia bothered him. He was greatly influenced by the renowned secular psychologist O. Hobart Mower who fustigated institutional psychiatry as bogus. An unbeliever, Mower was critical of Christianity for not taking more of a role in helping people with serious mental problems.

Mower believed that mental illness is primarily caused by the violation of conscience and unhealthy thinking. His premise has helped more people by far than any other psychological discipline and Adams witnessed this first hand. Mower’s influence provoked Adams to look into the Scriptures more deeply for God’s counsel regarding the deeper problems of life. This resulted in the publication of Competent to Counsel in 1970, and launched what is known today as the biblical counseling movement (BCM). Please note that this movement was picking up significant steam in the latter 80’s and early 90’s.

In 1970, the same year that the BCM was born, an extraordinary Reformed think tank was established by the name of The Australian Forum Project (AFP). Its theological journal, Present Truth, had a readership that exceeded all other theological journals in the English speaking world by the latter 70’s. Though the project died out in the early 80’s, it spawned a huge grassroots movement known as the “quiet revolution” of the “gospel resurgence.” The movement believed that it had recovered the true Reformation gospel that had been lost in Western culture over time, and frankly, they were absolutely correct about that.

The movement was covert, but spawned notable personalities such as John Piper over time. Piper exploded onto to the scene in 1986 with his book The Pleasures of God which promoted his Christian Hedonism theology. Unbeknown to most, this did not make Piper unique, the book is based on the same Martin Luther metaphysics that the AFP had rediscovered; he got it from them. At this point, the official contemporary name for the rediscovered Reformation gospel, the centrality of the objective gospel outside of us (Cogous), was taking a severe beating in Reformed circles. This is because contemporary Calvinists didn’t understand what Luther and Calvin really believed about the gospel.

John Piper looked to emerge from the movement as a legend because he had no direct ties to the AFP, but during the same time frame of his emergence, Cogous was also repackaged by a professor of theology at Westminster Theological Seminary. His name was John “Jack” Miller. Using the same doctrine, the authentic gospel of the Reformation, Miller developed the Sonship discipleship program. This also took a severe beating in Presbyterian circles. In fact, Jay Adams wrote a book against the movement in 1999. This was a debate between Calvinists in regard to what real Calvinism is. At any rate, Sonship changed its nomenclature to “Gospel Transformation” and went underground (2000). This started the gospel-everything movement. Sonship was saturated with the word “gospel” as an adjective for just about every word in the English language (“gospel centered this, gospel-driven that,” etc.). If anyone refuted what was being taught, they were speaking against the gospel; this was very effective.

If not for this change in strategy, John Piper would have been the only survivor of Cogous. Instead, with the help of two disciples of John Miller, David Powlison and Tim Keller, the Gospel Transformation movement gave birth to World Harvest Missions and the Acts 29 Network. It also injected life into the Emergent Church movement. Meanwhile, most thought the Sonship movement had been eliminated, but this was not the case at all. In 2006, a group of pastors that included this author tried to get a handle on a doctrine that was wreaking havoc on churches in the U.S. and spreading like wildfire. The doctrine had no name, so we dubbed it “Gospel Sanctification.” In 2008, the same movement was dubbed “New Calvinism” by society at large. In 2009, spiritual abuse blogs exploded in church culture as a direct cause of New Calvinism. We know now that the present-day New Calvinism movement was birthed by the AFP.

The Protestant Legacy of Weak Sanctification

The anti-Lordship Salvation movement came out of the controversy era of the 80’s. The following is the theses, parts 2 and 3 will articulate the theses. The theses could very well be dubbed The Denomination Myth. All of the camps involved in these Protestant debates share the same gospel, but differ on the application. The idea that the debate involves different gospels is a misnomer.

The Protestant Reformation gospel was predicated on the idea that the Christian life is used by God to finish our salvation. The official Protestant gospel is known as justification by faith. This is one of the most misunderstood terms in human history. Justification refers to God imputing His righteousness to those whom He saves. Many call this a forensic declaration by God. At this time, I am more comfortable saying that it is the imputation of God’s righteousness to the saved person as the idea of it being forensic; it’s something I have not investigated on my own albeit it’s a popular way of stating it. This is salvation…a righteous standing before God.

Sanctification, a setting apart for God’s holy purposes, is the Christian life. The Reformers saw sanctification as the progression of justification to a final justification. In Reformed circles, this is known as the “golden chain of salvation.” So, the Christian is saved, is being saved, and will be finally saved. Christians often say, “Sanctification is the growing part of salvation.” But really it isn’t, salvation doesn’t grow, this is a Protestant idea. The Christian life grows in wisdom and stature, but our salvation doesn’t grow, the two are totally separate. One is a finished work, and the other is a progression of personal maturity.

The Reformers were steeped in the ancient philosophy of the day that propagated the idea that the common man cannot properly understand reality, and this clearly reflected on their theology. The idea that grace is infused into man and enables him to properly understand reality would have been anathema according to their spiritual caste system of Platonist origins. This resulted in their progressive justification gospel. Justification by faith is a justification process by faith alone.

Every splinter group that came out of the Reformation founded their gospel on this premise. John Calvin believed that salvation was entering into a rest from works. He believed that sanctification is the Old Testament Sabbath rest (The Calvin Institutes 2.8.29). Hence, the Christian life is a rest from works. The Christian life must be lived the same way we were saved: by faith alone. Part 2 will explain why we are called to work in sanctification, and why it is not working for justification.

Another fact of the Reformation gospel is “righteousness” is defined as a perfect keeping of the law. To remove the law’s perfect standard, and its demands for perfection from justification is the very definition of antinomianism according to the Reformers. A perfect law-keeping must be maintained for each believer if they are to remain justified. Thirdly, this requires what is known as double imputation. Christ not only died for our sins so that our sins could be imputed to Him, He lived a life of perfect obedience to the law so that His obedience could be imputed to our sanctification. So, if we live our Christian life according to faith alone, justification will be finished the same way it started; hence, justification by faith. For purposes of this series, these will be the three pillars of the Reformed gospel that we will consider:

1. An unfinished justification.

2. Sabbath rest sanctification.

3. Double imputation.

As a result of this construct, Protestant sanctification has always been passive…and confused. Why? Humans are created to work, but work in sanctification is deemed to be working for justification because sanctification is the “growing part” of justification. Reformed academics like to say, “Justification and sanctification are never separate, but distinct.” Right, they are the same with the distinction being that one is the growing of the other. A baby who has grown into an adult is not separate from what he/she once was, but distinct from being a baby. Reformed academics constantly warn Christians to not live in a way that “makes the fruit of sanctification the root of justification.” John Piper warns us that the fruits of sanctification are the fruits of justification—all works in sanctification must flow from justification. Justification is a tree; justification is the roots, and sanctification is the fruits of justification. We are warned that working in sanctification can make “the fruit the root.” In essence, we are replacing the fruits of justification with our own fruit. This is sometimes referred to as “fruit stapling.”

How was the Reformation gospel lost?

To go along with its progressive justification, the Reformers also developed an interpretation method. The sole purpose of the Bible was to show us our constant need to have the perfect works of Jesus imputed to our lives by faith alone. The purpose of Scripture reading was to gain a deeper and deeper knowledge of our original need of salvation, i.e. “You need the gospel today as much as you needed it the day you were saved.” Indeed, so that the perfect obedience of Christ will continue to be applied to the law. This also applies to new sins we commit in the Christian life as well. Since we “sin in time,” we must also continue to receive forgiveness of new sins that we commit as Christians. So, the double imputation must be perpetually applied to the Christian life by faith alone. John Piper often speaks of how Christians continue to be saved by the gospel. This is in fact the Reformation gospel.

But over time, humanity’s natural bent to interpret the Scriptures grammatically instead of redemptively resulted in looking at justification and sanctification as being more separate, and spiritual growth being more connected to obedience. This created a hybrid Protestantism even among Calvinists. Nevertheless, the best results were the aforementioned living by biblical generalities. Yes, we “should” obey, but it’s optional. A popular idea in past years was a bi-level discipleship which was also optional.

This brings us to the crux of the issue.

Since the vast majority of Protestants see justification as a golden chain of salvation, two primary camps emerged:

A. Christ obeys the law for us.

B. Salvation cannot be based on a commitment—obedience must be optional.

Model A asserts that since we cannot keep the law perfectly, we must invoke the double imputation of Christ by faith alone in order to be saved and stay saved. Model B asserts that since the same gospel that saved us also sanctifies us, any commitment included in the gospel presentation must then be executed in sanctification to keep the process of justification moving forward. Therefore, obedience in sanctification must be completely optional. A consideration of works is just fruit stapling. If the Holy Spirit decides to do a work through someone, that’s His business and none of ours, “who are we to judge?”

This is simply two different executions of the same gospel. Model A does demand obedience because it assumes that Christians have faith, and that will result in manifestations of Christ’s obedience being imputed to our lives. Because this is mixed with our sinfulness, it is “subjective.” The actual term is “justification experienced subjectively”; objective justification, subjective justification, final justification (redefined justification, sanctification, and glorification). However, model B then interprets that as commitment that must be executed in the progressive part of salvation.

This is where the EB versus LS debate comes into play. This is a debate regarding execution of the same gospel while making the applications differing gospels. Out of this misunderstanding which came to a head in the 80’s, comes the anti-Lordship Salvation movement (ALS). Conversations with proponents of ALS reveal all of the same tenets of Cogous. First, there is the same idea of a final judgment in which sins committed by Christians will be covered by Jesus’ righteousness; “When God looks at us, all he will see is Jesus.” Secondly, there is the same idea of one law. Thirdly, there is the idea that our sins are covered and not ended.

They do differ on the “two natures.” Model A holds to the idea that Christians have the same totally depraved nature that they had when they were saved. Model B thinks the new birth supplies an additional Christ-like nature that fights with the old nature. Model A, aka Calvinists, actually think this is Romanism/Arminianism. Indeed, authentic Protestantism rejects the idea that any work of the Spirit is done IN the believer. Model B has several different takes on this including the idea that Christians are still dead, but the life of Jesus inside of them enables them to obey.

In part 2, we will examine why this construct is a false gospel, and why both parties are guilty. In part 3, we will examine the new birth and the idea that Christians have two natures.

paul

Why Catholicism and Protestantism Both are False Gospels

“This is not mere semantics concerning the best way to grow spiritually; what we believe about sanctification shows what we believe about justification. Is it a finished work or not? And if it isn’t, what we believe about sanctification is a purely salvific discussion by default anyway. The Reformers, new and old, do not frame sanctification in salvific terms; this is disingenuous and they know it. Confusion in regard to sanctification enables them to speak of sanctification in a justification way.”

“According to the Reformers, contemplative repentance is the fuel that powers our car on the justification highway to heaven. If we try to get to heaven any other way; i.e., some sort of belief that the highway is not a highway at all but a finished declaration and present reality, we lose justification and sanctification both (Michael Horton: Christless Christianity; p. 62).

In other words, contemplative repentance as a work that we do is the only way to heaven. Reformers like Tullian Tchividjian insist that it is Christ + Nothing = Everything; but again, that is because, like Calvin, he deems contemplative repentance as a non-work in sanctification that doesn’t cause our justification car to run out of gas. In fact, the think tank that launched the present-day Reformation resurgence framed it in those exact terms.”

Protestantism, which came from Catholicism, is also a false gospel. This is because Protestantism only reformed the means of progressive justification and didn’t reject it. Both are guilty of fusing justification and sanctification together. Therefore, both are false gospels because according to both, justification is not a finished work and progresses through sanctification. Therefore, the question of what man must believe so that justification is properly finished is the difference between heaven and hell. Salvation becomes a matter of the right justification process as opposed to simply believing on a finished work by God.

If sanctification (the Christian life) is the progressive expression of justification, man is involved in the justification process, and when this is the case, it is salvation by works because doing is involved even if the doing is believing only. Sanctification becomes a discussion about what is works in sanctification and what isn’t a work in sanctification, but doing something, whether believing or breathing, is a work; it’s all work. Hence, all of the confusion, and if you will, denominations. The propagation of sanctification by faith alone is always indicative of a justification that is not finished.

In truth, nothing we do in sanctification is a work for justification because that work is already finished. And this is the crux in regard to what Paul wrote to the Galatians:

Gal 3:1 – O foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you? It was before your eyes that Jesus Christ was publicly portrayed as crucified. 2 Let me ask you only this: Did you receive the Spirit by works of the law or by hearing with faith? 3 Are you so foolish? Having begun by the Spirit, are you now being perfected by the flesh?

“Being perfected” can be a little misleading if one does not examine this text carefully. The word for “perfected” is epiteleō which means “to complete, bring to an end.” This is why Young’s Literal Translation has it this way:

O thoughtless Galatians, who did bewitch you, not to obey the truth — before whose eyes Jesus Christ was described before among you crucified? 2 this only do I wish to learn from you — by works of law the Spirit did ye receive, or by the hearing of faith? 3 so thoughtless are ye! having begun in the Spirit, now in the flesh do ye end? [ESV Olive Tree footnote: “Or now ending with”].

The issue at hand was the fact that the Galatians were being influenced by the “circumcision party” (Gal 2:12). They taught salvation by circumcision. Paul called it justification by the law, but understand what he meant by that. The circumcision party emphasized justification by circumcision, but relaxed the rest of the law. Christ referred to this same sort of theology in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5:19). Paul’s point is that if you want to be justified by the law, all of the law must be kept perfectly in order to do so (Gal 4:2-4).

Freedom to obey the law aggressively (as love) in sanctification points to our view of justification. Aggressive obedience in sanctification points to the belief that justification is a finished work and unrelated to our work for God and others. It embraces the whole law and pursues righteousness for the sake of loving God and others truthfully. Though we fall short and that is disappointing, it cannot affect a work that is already finished: justification. Those misleading the Galatians taught that circumcision finished justification, and perhaps, as well, that any focus on the finer points of the law would circumvent the circumcision. In essence, those leading the Galatians astray were antinomians:

Gal 2:15 – We ourselves are Jews by birth and not Gentile sinners; 16 yet we know that a person is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ, so we also have believed in Christ Jesus, in order to be justified by faith in Christ and not by works of the law, because by works of the law no one will be justified.

17 But if, in our endeavor to be justified in Christ, we too were found to be sinners, is Christ then a servant of sin? Certainly not! 18 For if I rebuild what I tore down, I prove myself to be a transgressor. [parabatēs “lawbreaker”].

When justification and sanctification are fused together and sanctification is the progression of justification, invariably, some tradition or combination of traditions replaces a literal adherence to law. In other words, the law needs to be dumbed down because it is part of the justification process. So, mark it well: our attitude towards the law in sanctification reveals what we believe about justification:

Gal 5:7 – You were running well. Who hindered you from obeying the truth? 8 This persuasion is not from him who calls you.

They were “running” well. “Well” (kalōs) carries the idea of good morals. Paul was certainly NOT commending them for “running well” for justification. They replaced the law keeping of love in sanctification with the supposed fulfilment of justification by the traditions of men and their interpretation of the law. In this case, the primary tradition was circumcision. This is how the Amplified Bible states it:

Gal 3:2 – Let me ask you this one question: Did you receive the [Holy] Spirit as the result of obeying the Law and doing its works, or was it by hearing [the message of the Gospel] and believing [it]? [Was it from observing a law of rituals or from a message of faith?]

The paraphrase, “observing a law of rituals” is a good one. The Galatian error involved the necessary dumbing down of the law because the Christian life is seen as an extension of justification. To the contrary, there is NO law in justification because no man can withstand its judgment for righteousness (Rom 2:12, 3:19-21, 28, 4:15, 5:13, 6:14,15, 7:1, 6, 8 “Apart from the law, sin lies dead”). However, a relaxed view of the law of love in sanctification points to a law in justification that must be fulfilled by some sort of tradition:

Gal 5:6 – For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision counts for anything, but only faith working through love. 7 You were running well. Who hindered you from obeying the truth?

Notice that faith works (Jms 2:22) “through love,” and love fulfills the law (Rom13:8). This is a “running” by “obeying the truth.” This is why justification and sanctification must be completely separate. Justification is a finished work, and sanctification is a progressive work of love through obedience to the word of God.

Gospels that fuse justification and sanctification together always posit the idea that a striving to keep God’s law truthfully, as a way to earn salvation, is the pandemic of the day. That is not true at all. An effort to “run well” is always associated with the idea that the running has nothing to do with justification at all. Justification is God’s love to us and is finished; our love towards God and others is sanctification.

1Jn 4:19 – We love because he first loved us.

“We love” is sanctification. “He first loved us” is justification.

In both Romanism and Protestantism, justification is progressive, and sanctification is the progression of justification. This calls for a special formula that keeps us from circumventing the process. It also requires that we do something to maintain the process. “But Paul, doesn’t justification have a finished aspect and also a progressive aspect?” No, but even if that point is conceded, if justification isn’t properly finished, the beginning of it is for naught. In fact, this is exactly what John Calvin taught in regard to the perseverance of the saints. He stated that all who were chosen would not necessarily persevere to the end. Hence, their initial justification was for naught (CI 3.24.6-8).

The Protestant special formula is best exemplified in the writings of John Calvin. First, he made a perfect keeping of law the standard for justification. Justification was defined by a law standard. In the Calvin Institutes (CI), Calvin claimed that Christ obtained justification “by the whole course of his obedience” (CI 2.16.5). In the same section, Calvin interprets Christ’s one act of obedience (Rom 5:19) to the cross as pertaining to his whole life (that only refers to His obedience to the cross Pil 2:8). He also notes that Christ was “born under the law” (Gal 4:4,5) and offers that “proof” as well. But all that is saying is that Christ was born into the world like all other men: under the law. Christ is the only man born into the world that could withstand a judgment by the law—that doesn’t mean he had to keep it in order to fulfill all righteousness. For that matter, all righteousness was fulfilled when He was baptized by John the Baptist (Matt 3:15).

Calvin then goes on to explain that any law-keeping by the Christian is futile because we cannot keep it perfectly (CI 3.14. 10), and no Christian has ever done a work pleasing to God (CI 3.14.11). According to Calvin, the obedience of Christ must be continually applied to our lives until we get to heaven (Ibid). Furthermore, we must continually return to the same gospel that saved us for the forgiveness of new sins committed in the Christian life (Ibid, and CI 4.1.21,22).

So, the Protestant formula is returning to the same gospel that saved us in order to maintain our justification. Supposedly, it’s not of works because the initial repentance that saved us was by faith alone, so a perpetual returning to the same gospel maintains our justification while qualifying as faith alone. This, according to Calvin, does not circumvent the “Progressive” “Sense” of justification (see title: CI 3.14).

In this Protestant construct, Martin Luther’s alien righteousness was very important. This teaches that ALL righteousness remains outside of the believer. The believer has no righteousness of his own. This is important if you are on the justification bus going to glorification. Your inner righteousness would be part of the process that keeps the progression moving forward, perseverance if you will. This version of the Protestant formula to reach heaven by the same faith alone without works that saved/justified us can be seen in the Protestant concept of Sabbath Salvation. In the same way that the Israelites were not allowed to work on the Sabbath upon pain of death, anyone who works in their Christian life will suffer eternal death. Said Calvin:

Ezekiel is still more full, but the sum of what he says amounts to this: that the Sabbath is a sign by which Israel might know God is their sanctifier. If our sanctification consists in the mortification of our own will, the analogy between the external sign and the thing signified is most appropriate. We must rest entirely, in order that God may work in us; we must resign our own will, yield up our heart, and abandon all the lusts of the flesh. In short, we must desist from all the acts of our mind, that God working in us, we may rest in him (CI 2.8.29).

Calvin was adamant that none of God’s righteousness could be transferred to the believer (CI 3.14.11) in the “two-fold grace”(i.e., two-fold justification: Calvin deliberately used perceived synonyms to nuance what he believed) of justification and sanctification. All righteousness must remain outside of the believer. If the believer has no righteousness that is his/hers, they can continually affirm their belief in justification by faith alone and continue to receive forgiveness based on faith alone. In this way, Christ’s death and obedient life is perpetually applied to the believer in sanctification until they get to heaven (Ibid).

Therefore, it stands to reason that the only duty of the believer is to see their own sinfulness in sanctification; by doing this, they affirm they have no righteousness that is their own, and can do no work pleasing to God. According to the Protestant formula, this is the only work that is not a work. It is the “mortification of the will.” So, all work in sanctification must be the same repentance that originally saved us—this keeps us in the saving graces of God.

Contemporary Calvinists like John Piper refer to this as the Gospel continuing to save us IF we continue to “live by the gospel.” In a sermon titled, How Does the Gospel Save Believers? Part 2 Piper made the following statement:

We are asking the question, How does the gospel save believers?, not: How does the gospel get people to be believers? (August 16, 1998 by John Piper | Scripture: Romans 1:16-17 | Series: Romans: The Greatest Letter Ever Written).

So, let’s be clear, what we believe the gospel is, keeps us saved. The Protestant gospel is a sanctification defined by repentance only that keeps us saved. If we believe we have a righteousness of our own, all bets are off. Because sanctification is part of the “two-fold” grace (singular) of justification, man’s righteousness cannot participate. This is opposed to another view of the gospel that we are born again of God literally (1Jn 3:9, 5:18) and therefore righteous, and in fact full of goodness (Rom 15:14).

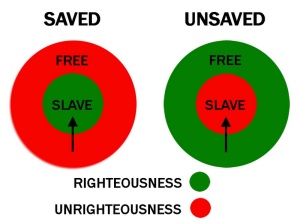

The fact that Christians still sin as mortals does not negate the fact that they are inherently righteous as proven by a change of direction. Certainly, perfection is the goal in sanctification, but not the standard for justification. The Bible explains it as an exchange of slavery. Those “under the law” and not “under grace” are free to do good, but enslaved to unrighteousness (Rom 6:20-22). Those under grace are enslaved to righteousness, but also free to sin (Rom 7:25). The chart below may help illustrate how this results in a change of life direction.

There is no law in justification, and it is a finished work apart from sanctification which fulfils the law by love. The law is now the standard for love in sanctification. As mentioned before, gospels that fuse justification and sanctification together in order to make justification an unfinished work often teach that obedience to the word of God circumvents the formula of salvation. In the case of Protestantism, a belief that we can please God by obeying His word assumes a righteousness that circumvents their gospel.

Hence, anything except repentance or mortification of the flesh assumes righteousness on our part. Regeneration (the new birth) must be manifested by the works of Christ alone in sanctification. There is no room here to expound on the point, but “obedience” in this construct is only an experience specifically called “vivification.” The “heart” of the believer is only changed in regard to its increased ability to experience Christ’s obedience. We experience the “active” obedience of Christ imputed to our sanctification (His “passive” obedience was His death on the cross), but we are not the ones doing it. This protestant idea can be seen in a statement by Calvinist Paul David Tripp:

When we think, desire, speak, or act in a right way, it isn’t time to pat ourselves on the back or cross it off our To Do List. Each time we do what is right, we are experiencing [underline added] what Christ has supplied for us (Paul David Tripp: How People Change; Punch Press 2006, p. 215).

John Calvin, as you will notice if you read his writings carefully, often replaced the idea of direct obedience to God with experiencing God’s works. This is very similar to the Gnostic idea of experiencing objective, or pure good subjectively. There are many variations of this throughout Protestantism, but at the very least, and in all cases, it will instigate a relaxed attitude towards the law.

And how does this relaxing of the law that Christ warned of take place? Simply stated, it takes the two-fold act of love which is sanctification, put off and put on (Eph 4:20-24), and makes them both the responsibility of Christ while we are mere experiencers of the manifestation. This is done by primarily making sanctification ALL about repentance only, but even then, it is for the purpose of more “seeing” via the “heart.” Hence, spiritual growth is defined by an increased capacity to experience Christ as opposed to being able to actually follow Him.

Therefore, the word of God is for gospel contemplationism, or better stated, repentive contemplationism, and is not actually applied to life by the kingdom citizen; that would be working for our justification. So, life application is defined as a work, and not working is defined as not a work; i.e., contemplationism is not a work. Essentially, this is the very construct Christ attacked in the Sermon on the Mount.

The Reformers, old and new, have always tried to do a metaphysical end around on this with “distinction without separation.” Unfortunately, Bible students who formidably challenged the Reformers and elicited this rebuttal in regard to the juxtaposing of justification and sanctification have been expunged from church history. The only detractors who get press were chosen by the Reformers because they had other problems theologically.

As a way to simplify this as much as possible, let’s focus on the fact that the likes of Calvin defined sanctification by repentance only. And remember, that repentance is only contemplationism as well. I will be using an article written by Cornelis P. Venema in the Mid-America Journal of Theology to make my points (Calvin’s Understanding of the “Two-Fold Grace of God” and Contemporary Ecumenical Discussion of the Gospel MJT 2007). I will underline what I want to emphasize.

The first part of Calvin’s basic formula for relating these two aspects of God’s grace [justification and sanctification] in Christ reflects his judgment that justification and sanctification concern two different questions, and denote two distinct facets of God’s relation to us. Whereas justification concerns the basis or reason for our salvation, sanctification concerns the way in which our life is converted to God (p. 79).

Note that justification is the beginning point of a “way” to “conversion” (salvation). Sanctification is the justification highway that leads to final salvation. Justification is not a finished work, it’s a starting point. The “distinction” is the beginning, or name of the highway project, and sanctification is the building project. But the Bible states that justification cannot be a building project because it is a finished work. This is not mere semantics concerning the best way to grow spiritually; what we believe about sanctification shows what we believe about justification. Is it a finished work or not? And if it isn’t, what we believe about sanctification is a purely salvific discussion by default anyway. The Reformers, new and old, do not frame sanctification in salvific terms; this is disingenuous and they know it. Confusion in regard to sanctification enables them to speak of sanctification in a justification way.

In addition, Calvin not only made repentive contemplationism the sum and substance of sanctification, but…

Throughout all of his writings—in his Institutes, commentaries, and sermons—Calvin consistently refers to this “double grace” or twofold benefit of our reception of the grace of God in Christ as comprising the “sum of the gospel.” These two benefits, justification and sanctification (or repentance) are the “two parts” of our redemption, both of which are bestowed upon us by Christ through faith. Together they form the two ways in which the “justice of God” is communicated to us, and in which we are cleansed by the holiness of Christ and made partakers of it. They constitute that “twofold cleansing” (double lavement), or “twofold purification” (duplex purgandi), which are granted to us by the Spirit of Christ. The “twofold grace of God” answers to the two ways in which Christ lives in us, and forms the invariable content of all Christian preaching about redemption in Christ and its application to human existence (p. 70).

Calvin usually terms the second benefit of our reception of God’s grace in Christ, “regeneration” (regeneratio) or “repentance” (poenitentia). Though inseparably joined with justification and faith, this benefit must not be confused with it. “As faith is not without hope, yet faith and hope are different things, so repentance and faith, although they are held together by a permanent bond, require to be joined rather than confused” (p. 76).

The author’s heavily footnoted assertions are correct (see source), Calvin, as with all of the Reformers, made repentance (actually, repentive contemplationism/contemplative repentance) synonymous with faith, grace, redemption, justification, sanctification, hope, purification, viz, a perpetual “’justice of God’…communicated to us.”

According to the Reformers, contemplative repentance is the fuel that powers our car on the justification highway to heaven. If we try to get to heaven any other way; i.e., some sort of belief that the highway is not a highway at all but a finished declaration and present reality, we lose justification and sanctification both (Michael Horton: Christless Christianity; p. 62).

In other words, contemplative repentance as a work that we do is the only way to heaven. It’s salvation by Christ plus contemplative repentance. Reformers like Tullian Tchividjian insist that it is Christ + Nothing = Everything, but again, that is because like Calvin, he deems contemplative repentance as a non-work in sanctification that doesn’t cause our justification car to run out of gas. In fact, the think tank that launched the present-day Reformation resurgence framed it in those exact terms.

We repeat, Justification is not a thing that we pass and get behind us. As Barth rightly said, it is not like a filling station that we pass but once. As we hold to its eschatological implications, justification by faith can never become static but must remain the dynamic center of Christian existence, the continuous present. We are always sinners in our eyes, but we are always standing on God’s justification and, perhaps more importantly, moving toward it. To be justified is a present-continuous miracle to the man who present-continuously believes, knowing that he who believes possesses all things, and he who does not believe possesses nothing. Such a life is only possible where the gospel of justification is continually heard and where God’s verdict of acquittal is like those mercies which Jeremiah declared were new every morning—”great is Thy faithfulness” (Lam. 3:22-23) [Present Truth Magazine: Righteousness by Faith (Part 4) Chapter 8 — The Eschatological Meaning of Justification; Volume Thirty-Five — Article 3].

In regard to another topic in which there is no room here, said think tank criticized contemporary Reformed thinkers for moving away from the original Reformation gospel which was salvation by justification plus contemplative repentance in sanctification. The specific criticism was against a gospel that perceived justification as being a finished work. Throughout the years, due to a misunderstanding of Reformed epistemology, those who fancied themselves as being of the Reformed camp gravitated to a separation of justification and sanctification, and justification being a finished work, and sanctification a progressive work by the believer and the Holy Spirit.

It has often been said, especially in the Reformed stream of thought, that justification is a once-and-for-all, nonrepeatable act… What inevitably happens in this way of viewing things is that justification becomes static. It becomes relegated (as far as the believing community is concerned) to a thing of the past. There is a tendency for it to become a warm memory (Ibid).

This has led to many contemporary quarrels between “Old” Calvinists and “New” Calvinists due to the fact that New Calvinism is a return to the authentic article. Most notably, the “Sonship” debate within Presbyterian circles and the New Covenant Theology debate within Reformed Baptist circles. This misunderstanding also led to debate in the contemporary biblical counseling movement where some Calvinists heavily emphasized obedience to the word of God, while Calvinists being influenced by the Resurgence called such emphasis in sanctification, “Phariseeism.”

Does the new birth make Christians righteous? Is the Holy Spirit’s power displayed in sanctification through our cooperative obedience and following? Is justification finished or not? Does sanctification have any connection to justification? And if it does, what? These questions, and the answers should be a line in the sand between the two gospels in our day.

In the summation of this point, what Calvin wrote specifically at times is very telling. Emphasis by underline added:

“…by new sins we continually separate ourselves, as far as we can, from the grace of God… Thus it is, that all the saints have need of the daily forgiveness of sins; for this alone keeps us in the family of God” (John Calvin: Commentaries on the Catholic Epistles; The Calvin Translation Society 1855. Editor: John Owen, p. 165 ¶4).

Nor by remission of sins does the Lord only once for all elect and admit us into the Church, but by the same means he preserves and defends us in it. For what would it avail us to receive a pardon of which we were afterwards to have no use? That the mercy of the Lord would be vain and delusive if only granted once, all the godly can bear witness; for there is none who is not conscious, during his whole life, of many infirmities which stand in need of divine mercy. And truly it is not without cause that the Lord promises this gift specially to his own household, nor in vain that he orders the same message of reconciliation to be daily delivered to them” (The Calvin Institutes: 4.1.21).

Calvin plainly states that “reconciliation” must be continually applied to cover new sins. Therefore, justification must be progressive; reconciliation IS justification—there is no justification without it. Instead of making peace with God once and entering into His family, reconciliation must be perpetual. At any given time that you think justification is a onetime event, you separate yourself from the “vital union” with Christ.

However, the Reformed end around on that is the idea that justification is a onetime event because it is both a declaration and a process. In one regard, it happened once, but in another regard, it keeps happening: “it’s a basis.” So, progressive justification is deceptively called “progressive sanctification.” Or, “Justification is the ground (basis) of our sanctification.” Right, because as stated also, “Sanctification is the fruit of justification.” This is deliberate deception. Certain words are used to mask the real Protestant gospel: salvation must be earned and maintained by a continual return to the same gospel that originally saved you.

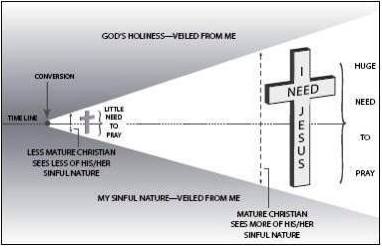

The following chart published by those of Reformed thought illustrates how contemplative repentance works:

Notice the emphasis on merely seeing (i.e., contemplationism). Furthermore, it’s antithetical to the biblical putting off and putting on prescribed by the Scriptures.

Catholicism is little different, it also fuses justification and sanctification together; justification is not a finished work. The following are excerpts from Catechism of the Catholic Church | Part 3, Life in Christ | Section 1, Man’s Vocation Life in the Spirit | Chapter 3, God’s Salvation: Law and Grace | Article 2, Grace and Justification: section…

1987: The grace of the Holy Spirit has the power to justify us, that is, to cleanse us from our sins and to communicate to us “the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ” and through Baptism.

Notice that there is an ongoing communication of righteousness to the believer which is Protestantesque. This is a perpetual imputation of justification. In theology, “righteousness” and “justification” are used interchangeably.

1988: Through the power of the Holy Spirit we take part in Christ’s Passion by dying to sin, and in his Resurrection by being born to a new life; we are members of his Body which is the Church, branches grafted onto the vine which is himself.

This is nothing more or less than the Protestant doctrine of mortification and vivification (see CI 3.3.2,9). Through confession, (mortification/repentance), we partake again in Christ’s passion resulting in a perpetual new birth experience symbolized/imputed initially by water baptism.

1989: The first work of the grace of the Holy Spirit is conversion, effecting justification in accordance with Jesus’ proclamation at the beginning of the Gospel: “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” Moved by grace, man turns toward God and away from sin, thus accepting forgiveness and righteousness from on high. Justification is not only the remission of sins, but also the sanctification and renewal of the interior man.

There is little ambiguity here; in Catholicism, like Protestantism, you are sanctified by justification…

1995: The Holy Spirit is the master of the interior life. By giving birth to the “inner man,” justification entails the sanctification of his whole being.

So, why the major beef between Catholicism and Protestantism? It boils down to “infused righteousness.” Romanism holds to the idea that the believer is enabled to participate in his/her final justification via confession and ritual. In the minds of Protestant theologians, that makes man a participant in justification. However, if all righteousness is outside of the believer and remains so, he/she is not a participant in the justification process. The same means, through contemplative repentance to communicate justification as an ongoing process is ok, but not the idea that the righteousness of God indwells the believer. It must be Luther’s alien righteousness. This is the way Calvinist John Piper presents the argument:

This meant the reversal of the relationship of sanctification to justification. Infused grace, beginning with baptismal regeneration, internalized the Gospel and made sanctification the basis of justification. This is an upside down Gospel (Desiring God blog: June 25, 2009; Goldsworthy on Why the Reformation Was Necessary).

When the ground of justification moves from Christ outside of us to the work of Christ inside of us, the gospel (and the human soul) is imperiled. It is an upside down gospel (Ibid).

In it [Goldsworthy’s lecture at Southern] it gave one of the clearest statements of why the Reformation was needed and what the problem was in the way the Roman Catholic church had conceived of the gospel….I would add that this ‘upside down’ gospel has not gone away—neither from Catholicism nor from Protestants (Ibid).

Romanism believes in an infused grace that enables the believer to partake in the justification process which is condoned because the beginning of justification is purely of God. The beginning of justification is pure grace, but sanctification is a “help”:

2025: We can have merit in God’s sight only because of God’s free plan to associate man with the work of his grace. Merit is to be ascribed in the first place to the grace of God, and secondly to man’s collaboration. Man’s merit is due to God.

2027: No one can merit the initial grace which is at the origin of conversion. Moved by the Holy Spirit, we can merit for ourselves and for others all the graces needed to attain eternal life, as well as necessary temporal goods.

This drove the Reformers berserk. In their construct, man, saved or otherwise, can have NO merit. It is fair to say that the main contention between the Reformers and Rome was metaphysical in nature. The crux of the contention was/is: How can man be found righteous at the end of his/her salvation journey?

This paper contends that there is NO salvation journey in regard to justification; it is a finished work. Only our lives as God’s children progress; the fact that we are part of God’s family is a complete, and settled issue. A person is born into a family once, and their growth does not increase their status as a family member; that was settled the day they were born.

Any gospel that posits justification as part of the sanctification process must necessarily involve man in the justification process, and the exclusion of works salvation is impossible. Everything becomes a work or doing something to MAINTAIN our justification. Even doing something passive that is not considered a work like thinking has a purpose, and that purpose can never be to complete a work that Christ has completed.

This is why Protestantism and Catholicism are both false gospels. It is a return to the Galatian error. Protestantism relaxes the law in sanctification to finish the finished work of justification by saying Christ obeys the law for us in sanctification if we live by faith alone in sanctification. Catholicism does its part in relaxing the law of love by replacing it with rituals in sanctification. Different means with the same purpose: to cooperate in the finishing of a finished work. That’s a false gospel.

The Reality of Reformed Theology

“Reformed theology, or if you will, Calvinism, is not a theological debate; it is a philosophical debate concerning the question of how we interpret reality itself.”

“Reformed theology, or if you will, Calvinism, is not a theological debate; it is a philosophical debate concerning the question of how we interpret reality itself.”

The philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, a proponent of ideas that I find disturbing, once stated the following: “In Christianity neither morality nor religion come into contact with reality at any point.” Perhaps he confused Christianity with the Reformation.

The fact that I agree with Nietzsche on this point is completely beside the point; the Reformers themselves stated exactly what Nietzsche said. To say that Luther stated in his Heidelberg Disputation that mankind in general, and Christians in particular are unable to understand reality or morality is beyond fair. Obviously, no belief touches anything it doesn’t believe in.

You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure any of this out, you only need to listen carefully: “The centrality of the objective gospel outside of us.” “The subjective power of an objective gospel.” “The Objective gospel.” “The objective gospel experienced subjectively.” These are all contemporary restatements of Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation. This is only complicated to those who have lost the art of asking themselves questions and knowing that words mean things.

When God created the earth and reality, he also created the epistemology to go along with it. He created light and said, that’s light. The word, “light” interprets what light is. Therefore, when someone talks about light, we understand what they are talking about. God even colabored with man to develop much of the epistemology by asking him to name the animals.

Then the serpent came along and in essence said to Eve, “Yea, has God really said, ‘That’s a cow’? Eve, you can’t draw conclusions through mere words, you need to go beyond that and see the knowledge of good and evil.” Likewise, Reformed teachers like Paul David Tripp teach that the literal meaning of words cannot interpret a “gospel context.” The likes of Rick Holland state that good grammar makes bad theology. Grab your metaphysical wallet and hold on to it tightly lest your philosophical pockets get picked.

The “objective gospel” (for instance, see objective gospel .org) is Luther’s cross story, and the subjectivity of it (how we experience the gospel) is Luther’s glory story.

Objective: (of a person or their judgment) not influenced by personal feelings or opinions in considering and representing facts.

Subjective: based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions.

One of the major tenants of the Heidelberg Disputation and Reformed theology in general is the idea that it is impossible for mankind in general and Christians in particular to approach ANY truth WITHOUT presuppositions; ie., subjectivism. Also, only the gospel is objective. ALL reality must be interpreted through redemption. Hence, the first tenet of New Covenant Theology which is a spinoff from Neo-Calvinism:

New Covenant Theology insists on the priority of Jesus Christ over all things, including history, revelation, and redemption. New Covenant Theology presumes a Christocentricity to the understanding and meaning of all reality.

Any questions? In case you do, consider this quote by the father of contemporary Reformed hermeneutics, Graeme Goldsworthy:

If the story is true, Jesus Christ is the interpretative key to every fact in the universe and, of course, the Bible is one such fact. He is thus the hermeneutic principle that applies first to the Bible as the ground for understanding, and also to the whole of reality (Graeme Goldsworthy: Gospel-centered Hermeneutics; p.48).

This is why the objective gospel, according to Reformed thought, must remain outside of us and only experienced through faith in it alone. This gospel alone must define who we are. The only thing man can know is that he is evil and God is good, EVERYTHING else is conformed to his own distorted individualist presuppositions. His life must be guided completely by something outside of him. Everything within is subjective. The idea that man can know anything objectively is Luther’s glory story. It’s all about the glory of man and not God. It’s either everything or nothing at all. If man has any merit or worth at all, he has ravaged God’s image. He must trust completely in the cross story. This is the foundation of the Calvin Institutes stated in 1.1.1. The Institutes are not only based specifically on Luther’s metaphysics, but the premise is eerily similar to the knowledge of good and evil propagated by the serpent.

The staple assertion during the infancy of the present Neo-Calvinist movement was the often heard idea that this new resurgence was needed because Evangelicalism was drowning in a “sea of subjectivism’:

Now, if the Fathers of the early church, so nearly removed in time from Paul, lost touch with the Pauline message, how much more is this true in succeeding generations? The powerful truth of righteousness by faith needs to be restated plainly, and understood clearly, by every new generation.

In our time we are awash in a “Sea of Subjectivism,” as one magazine put it over twenty years ago. Let me explain. In 1972 a publication known as Present Truth published the results of a survey with a five-point questionnaire which dealt with the most basic issues between the medieval church and the Reformation. Polling showed 95 per cent of the “Jesus People” were decidedly medieval and anti-Reformation in their doctrinal thinking about the gospel. Among church-going Protestants they found ratings nearly as high (The Highway blog: Article of the Month, Sola Fide: Does It Really Matter?; Dr. John H. Armstrong).

And what was the gist of that survey specifically? An illustration from the cited article follows:

Reformed theology, or if you will, Calvinism, is not a theological debate; it is a philosophical debate concerning the question of how we interpret reality itself. This is a question of whether or not man can comprehend reality, and the structuring of society accordingly. Throughout history, this debate has always ended up in an arena where life and death are determined. This is not a theological debate this is a debate that determines what kind of world we will be living in. Nietzsche was right in regard to a “Christian” nomenclature of Reformed thought; it holds to the idea that truth and morals are objective and unattainable while in this subjective world.

Reformed theology, or if you will, Calvinism, is not a theological debate; it is a philosophical debate concerning the question of how we interpret reality itself. This is a question of whether or not man can comprehend reality, and the structuring of society accordingly. Throughout history, this debate has always ended up in an arena where life and death are determined. This is not a theological debate this is a debate that determines what kind of world we will be living in. Nietzsche was right in regard to a “Christian” nomenclature of Reformed thought; it holds to the idea that truth and morals are objective and unattainable while in this subjective world.

paul

1 comment